Scenario #1: “Gravity is a natural force that pulls all objects toward the center of the earth. If I let go of my pen, BOOM, it falls to my desk every time.”

Scenario #2: “I see my pen fall when I let go of it, but I have also seen birds and airplanes and clouds float high above the world. Probably my pen will fall when I let go of it, but just maybe . . .”

#1 is deductive reasoning—stating a general principle, then backing it up with evidence. Deductive reasoning is certainty.

#2 is inductive reasoning—looking at individual pieces of evidence and stating a probability, not a certainty, because there are also some observed exceptions.

This difference in thinking may be the basis for why lawyers are perplexed by some verdicts: Lawyers think deductively and are certain that the evidence shows their side is right. Jurors think inductively, bringing all their personal exceptions into the deliberation room, hidden in their brains until the discussion begins.

Lawyers and jurors think differently.

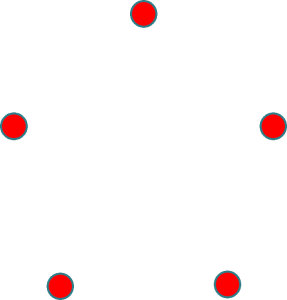

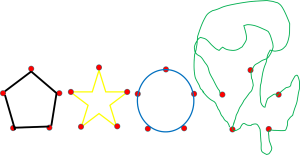

For instance, let me present 5 case facts depicted graphically:

The deductive thinker flashes back to geometry class and remembers that a 5-sided object with straight sides and equal distances between its corners is a simple pentagon. The internal angles always equal 540°. Even without sides drawn in, the shape is unmistakable—to a lawyer.

Four inductive-thinking jurors, though, get all those same facts in the same arrangement, grab a donut on the way into the deliberation room, sit down confidently and, in turn:

The teacher says: The Hollywood Wanna-Be says: The jeweler says: The Assistant Manager at the Dispensary says:

The lawyer was right. It’s a pentagon. The lawyer was wrong. It’s a star. Are you nuts? It’s a ring! It’s organic, dude [there’s always one in every room]

Inductive thinking allows for personal experiences to mix with the facts, creating probability, not certainty. Their view of the facts is not wrong, it is just tempered by all the exceptions that hide in their individual life of experiences. Birds and airplanes and clouds DO all come back to earth at some point because they are all subject to the law of gravity, but inductive thinkers see that only as a probability because they don’t always see the outcome.

Instead of graphic dots, let’s look at a real-life case example. Your 5 facts are:

- The public purpose is for a property the County needs to use for gray water run-off

- “Taking” as in the 5th Amendment

- The date of valuation is March 5, 2016

- The highest and best use is a custom home community with a golf course

- Just Compensation is $15.9 million

Ask the deductive and inductive thinkers one simple question: “What kind of case is this?”

Deductive thinkers: “Eminent Domain case!” — Lawyers immediately know the general principles, rules, and laws that tie all these facts into a neat bundle, a certain package.

Inductive thinkers: “What?” – they see the facts, but they are just a loose collection of stuff – no meaning is attached.

What can turn this meaninglessness into certainty?

Attorneys need to:

- Recognize this different style of juror thinking—that the facts do not “obviously” mean to a juror what they mean to a lawyer;

- Accept this different style of juror thinking as reasonable [not automatically wrong or stupid or ill-informed];

- Create a story with a theme that ties the facts together in the way YOU want them tied together. If you leave the conclusion up to the individual jurors, you get a hodge-podge of probability and UN-certainty. Giving them a good story makes it easy for them to see the picture the right way—your way.

We can’t make other people think like we do, but we can be most persuasive when we recognize the our differences and adapt our thinking to facilitate theirs.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Click below to add your email address to our mailing list and receive the latest Persuasion Tips right in your inbox!