Trials take place because, at some point in the past, the parties each made some sort of decision that altered the “usual” flow of life. A conflict was created by these divergent decisions. A jury, though, the body charged with resolving this divergence, has a very different perspective on those decisions: The jury has the benefit/curse of 20/20 hindsight, a perspective not available to the parties at the times their decisions were made. How can you teach the jury to put themselves in the parties’ shoes AT THE TIME THE DECISION WAS MADE?

Well, Maxi can teach them how to wrestle with this difficult task.

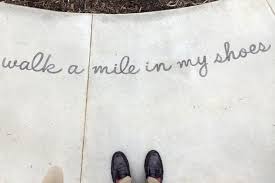

Developmental researchers Wimmer and Perner [1983]* used the story of Maxi to find out when children can begin to know what another person knows. They told a variety of 3 to 9 year olds the story of Maxi. Maxi had some chocolate that he wanted to eat later, so before he went out to play, he put it in the blue cupboard in the kitchen. Then he went out to play. While he was out, Maxi’s mom wanted to make a cake and used some of Maxi’s chocolate to do so. She put the unused chocolate back into the green cupboard in the cabinet. The kids in the experiment were then asked, “When Maxi comes back from the playground and wants his chocolate, where would he look for it?” It turns out that kids four and under always say “in the green cabinet,” but kids six and over are able to say, “in the blue cabinet.” They know he won’t find it there, but they are able to understand what Maxi knew at the time he re-entered the kitchen. Even when they know Maxi will be wrong and will need to look elsewhere, they can “understand” his wrong decision because they can relate to what he knew at the time. They are able to place themselves in Maxi’s shoes at the moment of his decision.

Let’s look at some decisions that led to trials:

- A plaintiff is injured because he decides to drive into an intersection that is not clear yet, but he was unable to see that it was unclear;

- A defendant decides to deny an insurance claim because there seems to be a problem with the original application;

- A plaintiff trusts her long-time doctor and decides to embark on a difficult course of treatment that, it turns out, she never needed because the doctor did not first do the definitive test to see if she had the condition;

All these are instances where jurors, using 20/20 hindsight say things like, “he should have crept out into the intersection first,” or “they should have asked the insured about the discrepancy before they denied the claim,” or “she should have insisted on a second opinion”—and all of those hindsight perspectives are probably correct. However, the conflict in the case is over what the party knew at the time the decision was made, not what we all know now.

It is common for a judge or an attorney to tell jurors to come to a decision not in hindsight, but with what was known at the time. In the abstract, I have watched focus group participants and mock jurors struggle with this concept mightily, but to no avail. However, telling the jury the story of Maxi and explaining the results of this simple experiment suddenly makes the concept very clear, simple, and manageable. It only takes one juror to “get” this concept to keep the rest of the group on track.

And, without saying so, you are subtly challenging the jurors not be 4-year olds, but are asking them to look at a decision at least in the way that a 6-year old might!

*Wimmer, Heinz, and Perner, Josef. [1983]. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition. Vol. 13, Issue 1, pp. 103-128.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Click below to add your email address to our mailing list and receive the latest Persuasion Tips right in your inbox!