I think about your courtroom challenges all the time. For instance, last week, I was lying on the operating table in my paper gown, waiting for surgery to begin. On the wall was a sign that said, “Did you take a time-out?” I instantly thought, “That’s like from the ‘The Checklist Manifesto’ by Atul Gawande [2009, Henry Holt and Company, publishers]! Brilliant book! Hey! What if trial attorneys could use a strategy like that during a dangerous part of their trials, like during

voir dirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrre?”

Then the world got all squiggly like in a movie when someone is going to sleep or entering a flashback. The anesthesia overwhelmed my last remaining brain cells, eradicating all memory of my thought until today.

I think.

Dr. Gawande’s book presents solid data on how simple checklists are used effectively to reduce surgical errors. The “time-out” sign I saw was a reminder to me to ask the surgical team to engage with their checklist. Asking that question was on MY pre-surgical checklist of things to do on the day of surgery. It was supposed to get the team to stop, take a deep breath, and look at the chart and my arm-band one more time to make sure I was the right person there to receive the right treatment on the right part of my body. It only takes a few seconds to make sure that the good decisions are being made when the pressure is high.

Pilots have used checklists since humans began to fly. Checklists are good when there is no room for error.

Voir dire, then, is the perfect place for trial attorneys to use one. Exercising challenges to the panel is a high-pressure, rapid-fire, decision-making time that has profound consequences. Why wouldn’t a checklist be helpful?

You have done focus groups and mock trials on this case. You have years of experience with various types of jurors. From all of that research and experience, you know the 5-10 factors that make a person good or bad for your side in this case. So, what do I see lots of trial attorneys do to arrive at their crucial challenge decisions?

- They look at their tiny, illegible notes on the court-issued seating chart, some of which are crossed out from a prior juror being excused;

- They check their sticky note scribbles;

- They try to remember which juror was the “good-looking one” or who was the one who “said that terrible thing.”

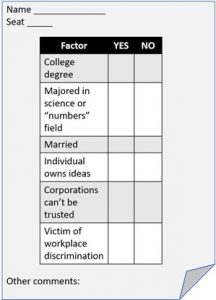

OK, but what if you had a checklist for each juror that had the characteristics of your “ideal juror” right on it? The checklist could look something like this:

How could this work in real time?

- A juror gets called into the box;

- You pull out a blank checklist sheet [which could be as small as a note card, pre-printed in your office];

- You write their name and seat at the top;

- You can spread them out on your table in place of the seating chart and move among them quickly as jurors respond to questions;

- You listen during your questioning and the opposition questioning, checking off a “yes” or “no” on each important factor that you hear;

- A juror gets excused for cause—you discretely toss their checklist and start a new one for the replacement juror;

- You use the checklist as your reminder to ask certain jurors about the factors that you might have forgotten to cover with them;

- You jot down notes in the “Other” section;

- When you get to discuss challenges with your team, the checklist becomes your “scorecard.” People who have more yes’s are more like your ideal juror. People with more no’s are not as likely to be your type and need to be discussed with your team.

Instead of paper, this format could be put on a laptop spreadsheet for quick review at your team’s challenge conference.

Some version of this idea would help

- Maintain your focus on what is important in a juror for this case.

- Keep you organized and thorough in your questioning.

- Trigger your memory as to what individuals said on different topics of importance.

- Give you data for comparing one juror to another when you have to decide between two people [“she has 2 yes’s and he only has one”].

- Help you separate your “gut instinct” from the reality of the situation. Subjective and objective factors are both important to consider, but a checklist helps you to keep them separate so you know why are deciding the way you are deciding.

On the other hand, I may still be under anesthesia and this whole Persuasion Tip © is just a narcotic trip. We’ll never know.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Click below to add your email address to our mailing list and receive the latest Persuasion Tips right in your inbox!